Self-supervised Learning

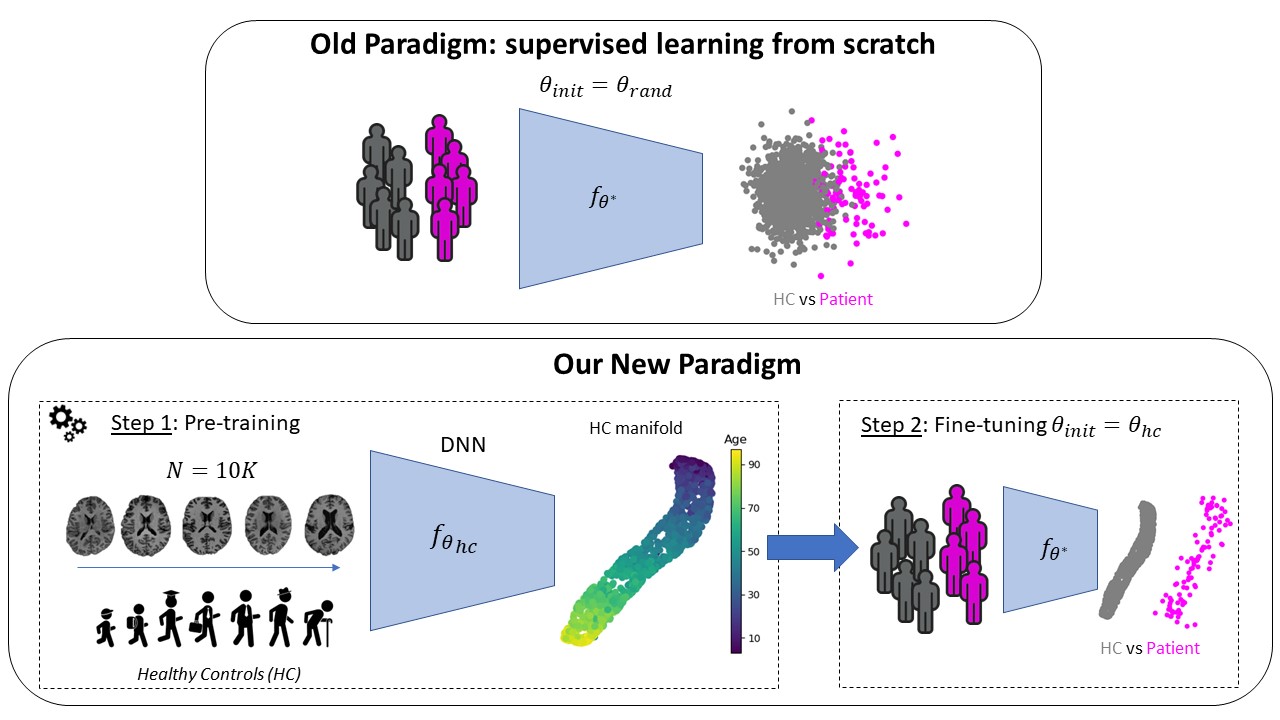

Context Many specific tasks in Computer Vision, such as object detection (e.g., YOLOv71), image classification (e.g., ResNet-50), or semantic segmentation (e.g., UNet, Swin Transformer) have reached astonishing results in the last years. This has been possible mainly because large (N > \(10^6\)), labeled data-sets were easily accessible and freely available. However, many applications in medical imaging lack such large datasets and annotation might be very time-consuming and difficult even for experienced medical doctors. For instance, predicting mental or neurodevelopmental disorders from neuroanatomical imaging data (e.g., T1-w MRI) has not yet achieved the expected results (i.e., AUC ≥ 90 (Dufumier et al., 2024)). Furthermore, recent studies yielded contradictory results when comparing Deep Learning with Standard Machine Learning (SML) on top of classical feature extraction (Dufumier et al., 2024).

Challenges The first challenge concerns the small number of pathological samples. In supervised learning, when dealing with a small labeled dataset, the most used and well-known solution is supervised Transfer Learning from ImageNet (or other large vision datasets). However, it has been recently shown that this strategy is useful, namely features are re-used, only when there is a high visual similarity between the pre-train and target domain (e.g., low Fréchet inception distance (FID)). This is not the case when comparing natural and medical images. Furthermore, many medical images, and in particular brain MRI scans, are 3D volumes, differently from the 2D images of ImageNet. This entails a great domain gap between the large labeled datasets used in computer vision and medical images. Another approach comprises self-supervised learning (SSL) methods which leverage an annotation-free pretext task to provide a surrogate supervision signal for feature learning. Nonetheless, these methods still need large (unannotated) datasets, which should comprise, to reduce the domain gap, data similar to the ones in the (labeled) target dataset, namely pathological patients. However, the large majority of images currently stored in hospitals and clinical laboratories belong to healthy subjects. Indeed, the largest datasets currently available (e.g., UKBioBank and OpenBHB) mostly contain data of healthy subjects. Furthermore, these datasets usually comprise one or multiple imaging modalities, as well as clinical data, such as age, gender and weight. The research challenge thus becomes how to leverage large datasets of healthy subjects and combine the heterogeneous sources of information (i.e., clinical and imaging data) to improve the diagnostic and understanding of patients.

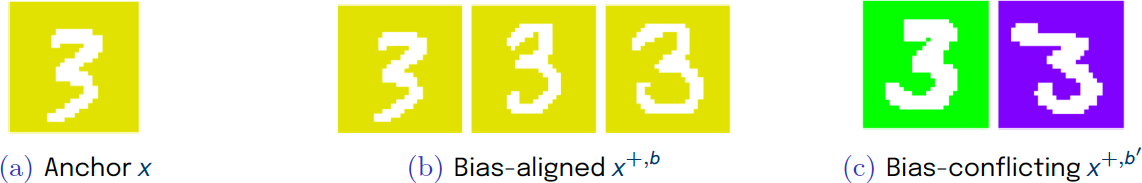

A second challenge concerns the data biases. In our work, we define data biases as the visual patterns that correlate with the target task and/or are easy to learn, but are not relevant for the target task. For instance, the site effect in MRI images refers to systematic variations or discrepancies in feature distributions across different imaging sites, that arise from differences in equipment, protocols, or settings , and are not related to a disease (i.e., target task). When working with MRI samples in a binary classification problem (healthy Vs patients), these spurious differences can be visually more accentuated, and thus easy to learn, than the relevant differences between the two classes. This can result in a biased model, whose predictions majorly rely on the bias attributes and not on the true, generalizable, and discriminative features.

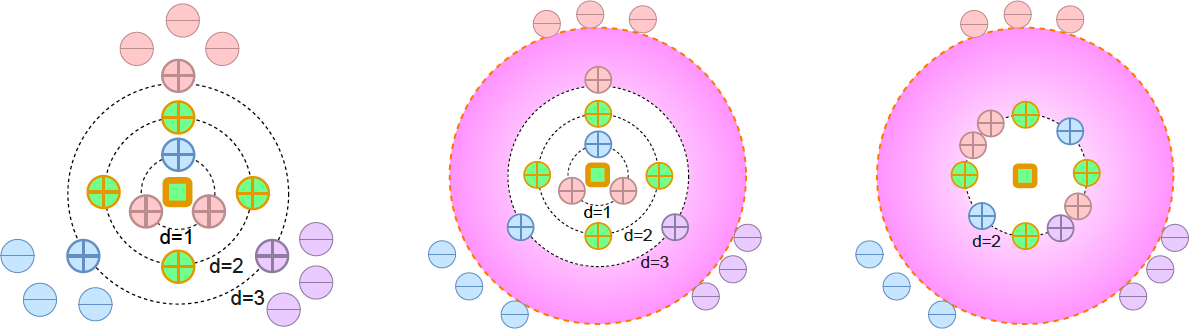

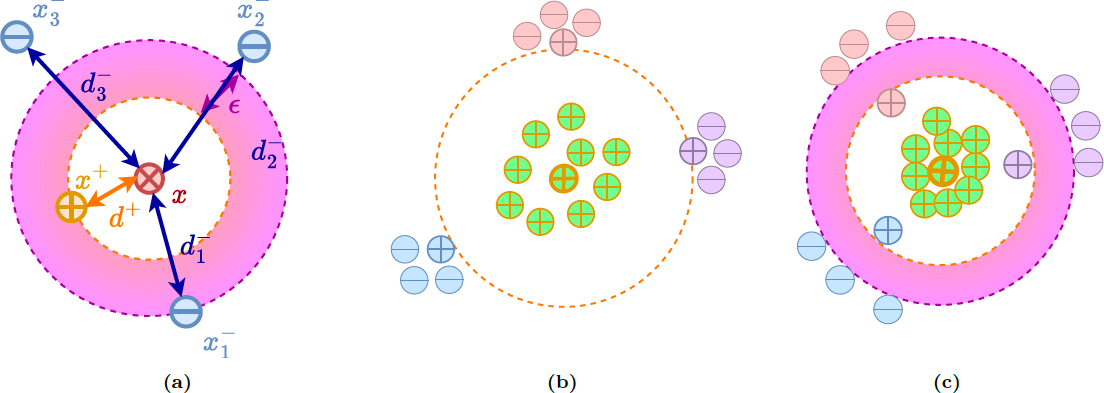

Contributions In this project, we have proposed a new geometric approach for contrastive learning (Barbano et al., 2023) that can be used in different settings:

- unsupervised (i.e., no labels) (Sarfati et al., 2023), (Ruppli et al., 2022), (Barbano et al., 2023),

- supervised (i.e., class labels) (Barbano et al., 2023), and

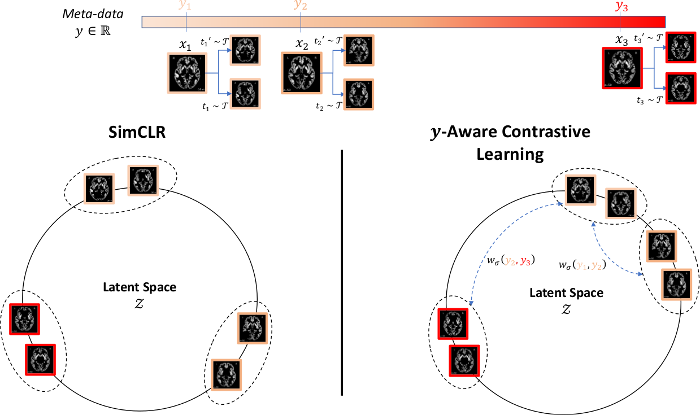

- weakly-supervised (i.e., weak attributes or regression) (Dufumier et al., 2021) (Barbano et al., 2023) (Dufumier et al., 2023), (Ruppli et al., 2023), (Dufumier et al., 2021).

It is well adapted to integrate prior information, such as weak attributes or representations learned from generative models, and can thus be used to learn a representation of the healthy population by leveraging both clinical and imaging data.

Based on the proposed geometric approach, we show why recent contrastive losses (InfoNCE, SupCon, etc.) can fail when dealing with biased data and derive a new debiasing regularization loss, that work well even with extremely biased data. (Barbano et al., 2023). You can find a visual explanation below using the color-MNIST dataset.