Context:

Overview:

Overview:

git mv is usually not required. If you just move files around within the working directory, git SHOULD be able to detect the moves and keep the history of the files.

SHOULD! If you do not want to take the risk, or want to do moves that you know will result in ambiguities, then use git mv

Rename detection can be disabled in the configuration.

git diff = what are the changes between the working directory and the local repository

git diff branch2 = what are the changes from the current branch to branch2

Imagine somebody committed something new, and you want to check what this person did without checking out.

git diff distant/current if your checked out branch is "current"

diff --git a/src/Main.java b/src/Main.java

index a0428da..f515cbb 100644

--- a/src/Main.java

+++ b/src/Main.java

@@ -1,6 +1,6 @@

public class Main {

public static void main(String[] args) {

- System.out.println("Hello World!");

+ System.out.println("Bonjour!");

}

}Merge and rebase are two ways to merge changes from two branches (or two states).

|

The principle, graphically:

|

What happens with the two commands is the exact opposite:

Merge: you are on master, the destination of the merge, and you do Rebase: you are on feature, the branch you want to merge, and you do |

There has to be a common commit for a merge to be allowed.

Pros and cons:

Rewriting history is moving commits around the tree in the repo.

If the part of history you are rewriting has not been pushed, i.e. not shared with anyone, then everything is fine.

If it was pushed, but no one is using it, then fine.

If it was pushed, and someone based one or more commits onto what you are changing, then THEY will have a problem: when they pull, a mess appears and they do not have access to the info about what happened.

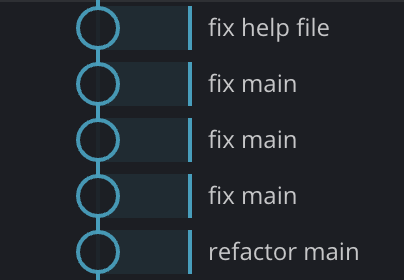

You have many small commits, one for each of your attempts to fix one elusive bug.

Either you go into a GIT GUI and select the 3 commits and then squash, or you do:

git rebase -i master

then replace 'pick' by 'squash' for all commits but the first to get something like this:

Cherrypick is an option of merge where you can pick which commit you want to integrate during a merge and which commit is ignored. For example, your v2 branch includes one commit that fixes a bug also in v1. You can create a v1plus with v1 + only one commit from v2.

Either you go into a GIT GUI and select cherrypick, or you do:

git rebase -i master

then replace 'pick' by 'skip' for the commits you want to ignore.

This method also allows you to reorder commits. I never had to do it.

Github/gitlab evolved from a git server and added a web interface to:

In the ~/.ssh folder, the config file contains:

Host gitlab.enst.fr

IdentityFile ~/.ssh/gitkraken_rsa

IdentitiesOnly yesThis file indicates, per git site, which SSH key to use to connect.

Git has other "central" configuration with a loooong list of fields:

git config --global user.name "JC Dufourd" Configuration can be machine-wide (file somewhere in the system), account-wide (file ~/.gitconfig) or just for the current folder (file .git/config).

Use git config --system or git config --global or git config --local respectively.

You have added everything in the folder to the repository including the *.class.

Edit the file .gitignore to add *.class

git rm *.class

Then commit

Files used by your IDE (Eclipse, IntelliJ, Atom...) may still be better untracked, but not deleted like the *.class.

Edit the file .gitignore to add these files

git rm --cached .idea/*

Then commit

Open Terminal.

Create a bare clone of the repository.

$ git clone --bare https://github.com/exampleuser/old-repository.gitMirror-push to the new repository.

$ cd old-repository.git

$ git push --mirror https://github.com/exampleuser/new-repository.gitRemove the temporary local repository you created in step 1.

$ cd ..

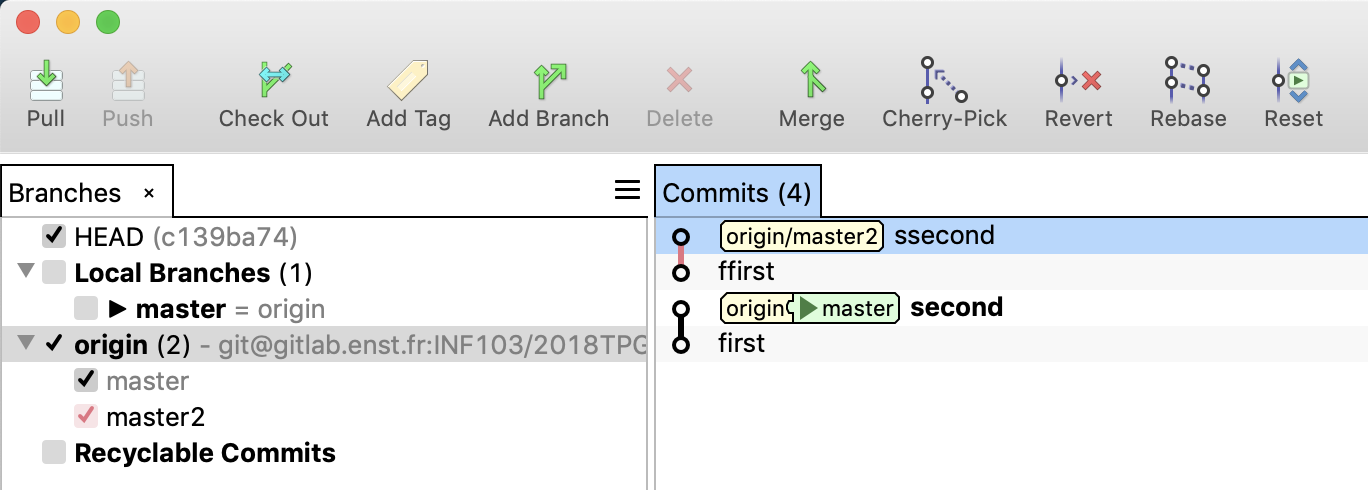

$ rm -rf old-repositoryYou have two branches you want to merge. You get a message about unrelated histories. What happened ?

One possible scenario is one person A did git init, git commit, git remote add, git push on a certain distant repo. A person B did git init, git commit, git remote add on the same distant repo. Then B did git push, got an error saying that you cannot push to master, and then B changed the name of the local master to master2, then tried pushing again.

Here the repo history looks like this:

There is no common commit but two separate commit lines, instead of one tree. By default, git thinks a merge should not happen: all its tools rely on the existence of a common commit.

If you are sure the two branches are mergeable meaningfully, then you can force a merge.

Try the merge command again, this time with the option --allow-unrelated-histories

There was an exception in function XYZ, you fixed the bug, but you had to change the behaviour of the function, which is used in many places.

You want to know where the keyword XYZ appears in the project, regardless of folder or branch.

git grep XYZ

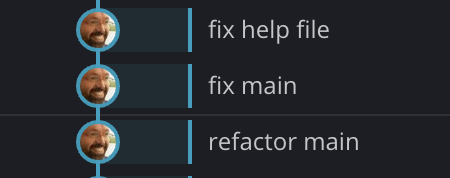

Sometimes, you are looking at code, there is no comment, you have no idea what it does or why. And you want to know who wrote these lines and when.

git blame file types the file with each line annotated with who, when, which commit

I have never used it on the command line, but it is pretty handy in an IDE.

Sometimes, you are doing a long merge, you solved 200 conflicts and on the last file, you realize something is wrong. The guy responsible for the changes missed something, you have to abort the merge and tell him to fix the problem.

He does, and you start merging, solving again the same 200 conflicts.

GIT has a tool to help with that: ReReRe for "reuse recorder resolutions"

First, configure it:

git config rerere.enabled true

Then cleanup before doing the first merge: git rerere clear

Then first merge, abort, rework, you start the second merge: every conflict that you already solved is solved automatically, and the first action you have to make is on the last file which was not yet merged.

Git hooks are scripts that Git executes before or after events such as: commit, push, and receive. Git hooks are a built-in feature - no need to download anything. Git hooks are run locally.

These hook scripts are only limited by your imagination. Some example hook scripts include:

The hooks are all stored in the hooks subdirectory of the Git directory. In most projects, that’s .git/hooks

Look at .sample files in this directory.

Note: a pre-commit hook can be bypassed by git commit --no-verify so it is not a perfect weapon against lazy team mates.

Other courses in this series are:

This course was designed by Jean-Claude Dufourd, and shared as Creative Commons 3, BY-NC-SA (attribution, non commercial, share alike)